Last week we talked about the social nature of the problem-framing process — or to phrase that in a way that isn’t hopelessly academic, how we define “what is good” together. A workflow that tries to increase velocity by skipping that process will always fail.

But, you might ask — can’t we win some velocity within that problem-framing process? Everyone knows research takes too long and only ends up telling us what we already know anyway (these are extremely common research myths which Jon Yablonski has already debunked) so can’t we use AI to help generate alignment faster?

The short answer is: no.

A recent post by Erika Hall neatly encapsulates the problem:

We already ignore so much of the information we have at our literal fingertips because the thing that takes time is bringing a group of decision-makers around to a shared view of reality … [research] isn't just a means to generate insights, it's a method for grounding an organization in the real world with shared accountability to the evidence.

The challenge is not data but alignment

Stakeholders will tell you “we need more data” but that’s not a fact; that’s just their (incorrect) diagnosis of the situation, because they don’t think about the difference between data and knowledge.

For most people, there is no difference between the world and their mental model of the world; things that are “unintuitive” because they were not explained correctly can suddenly become intuitive with a different explanation, even though the thing itself did not change. Similarly, stakeholders might either dismiss a fact as an outlier or latch on to it as the driver behind a massive investment — not because the fact changed, but because their mental model changed to one that could accommodate it.

In other words, research is not done when a fact is produced. It is done when the fact has become knowledge — a process that requires creating not only facts but alignment. Influencing stakeholders is not a distraction; it is the work.

The popular perspective of “pick a strategy and then do research” is thus entirely backwards; forming the understanding comes first, because it defines what problems it is even possible for stakeholders to perceive, and therefore form a project around.

But then we run into the same problem we did last week: qualitative insights are harder to capture and fit into the stakeholder mental model which calls for more numbers, more information, more efficiency.

The worldview of technopoly is captured in Frederick Taylor’s principles of scientific management: 1) the primary goal of work is efficiency; 2) technical calculation is always to be preferred over human judgment, which is not trustworthy; 3) subjectivity is the enemy of clarity of thought; 4) what cannot be measured can be safely ignored, because it either does not exist, or it has no value

But “more and more data!” has the same problem as “more and more features!” — it’s missing the “so what.” Elevating data gathering above all other activities limits your possible interpretation of that data to a validation exercise.

Alignment = Understanding = Ownership

What your stakeholders are looking for isn’t the most accurate data, but a conclusion that can be understood within their mental model. “Doing research” involves not only gathering that data for stakeholders to look at, but shaping their mental models to be able to accommodate that conclusion.

We can think of this as a ladder, because everyone loves a good visual metaphor:

The first rung of the ladder is simply presenting a fact; this is the level of engagement you can expect from a dashboard and only allows a stakeholder to reinforce their existing mental model;

The second rung of this ladder is presenting a conclusion that the fact allows you to make; this has the opportunity to shape the stakeholder’s mental model but the conclusion can also be rejected if it’s incompatible with the prevailing mental model;

The third rung of the ladder is constructing a mental model over time, rather than during a single touchpoint. This created a sense of ownership of the conclusions that can be drawn; stakeholders are now comfortable not just repeating the conclusion but driving projects based on it.

That sense of ownership can only be built up gradually, though a prolonged period of collaboration and establishing trust. It’s an emotional connection: learning new things is exciting. This process imparts a quality of aliveness onto its output, which keeps the energy going even when a powerful executive isn’t in the room to drive it.

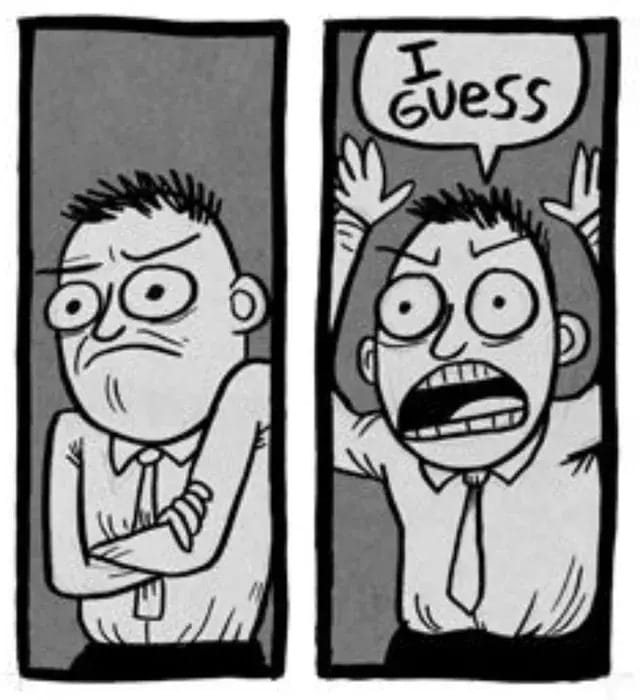

You’re not looking for “ok, I guess.” You’re looking for “LET’S GO.”

The meme from this comic, or: what you don’t want your stakeholders to look like.

AI is an alignment-killer

This is why AI can’t meaningfully help you with this process: the sense of alignment it creates is entirely illusory.

Not only are AI-generated analyses unreliable but no one is going to be reading them; the more AI had a hand in producing a text, the less likely it is that even the author will remember what it said. But of course, we’re not even being encouraged to read AI text; but “summarize” it for our own consumption, which introduces yet another well-documented point of failure.

A summary enriches a text by providing context and external concepts, creating a broader framework for understanding. Shortening, in contrast, only reduces the original text; it removes information without adding any new perspective.

The more AI is involved in problem framing, the lower you go on that maturity ladder; the focus on human mental models becomes replaced by simple shortening logic. Any chance of generating a sense of ownership is gone, because the humans are not active participants in the process of knowledge creation. Instead, the prevailing dynamic is that they are research assistants to the LLM. At the end of the day they may accept its conclusion, but it does not belong to them.

And the conclusions AI can arrive at are, frankly, not very impressive. As a statistical model based on existing sources, AI crushes divergent thinking. It can help us bring about only the most obvious futures, while distancing us from the unlikely ones that we may find desirable if we only knew that they were an option. AI reproduces biases that we know are harmful; attempts to address those AI biases either fail or are simply shot down outright.

‘AI futurism’ does not show us how to shape the future, but rather prevents us from taking action in the present.

If all you want to do is clock in at the feature factory, then all of this probably sounds just fine. At the end of the day there will be plenty of other designers at the bar to commiserate with you about how stakeholders just don’t understand the value of your great designerly taste.

— Pavel at the Product Picnic