The foundational myth of our practice looks something like this: we find a big problem, we have an idea that can solve it, and executing on that idea unlocks orders of magnitude in measurable improvement. This is actually a humanities skill, called problematization, but never mind that for now.

For those of you who are hockey fans, or perhaps just fans of Heated Rivalry, Jen Briselli has a great new piece on how the game is a microcosm of a complex system. Every actor in that system has to anticipate not only the movement of a puck, but the movement of everyone else. Success comes not solely from technical skill, but also from positioning yourself to exploit multiple opportunities.

The whole piece is well worth your time. But there’s one quote in particular that is relevant to our Picnic:

Hockey punishes players who rely on ideal conditions, because ideal conditions are rare. The game demands that you see what’s happening, not just what’s supposed to happen.

Sounds familiar? It’s exactly this skill that actually lets a player “skate to where the puck is going to be.” If you assume that everything is perfectly going to follow your ten-step plan, you’re likely to find yourself on the opposite side of the rink from where all the action is.

This is where most product teams are. They are told “don’t overthink it.” They are told to build before they measure and learn. And so they must rely on their sense of what is supposed to happen; they solutioneer for imagined use cases.

Under this paradigm, research is limited to confirmation bias. Rather than being an ongoing activity of sensing, it is a one-off box checking exercise. Consultation happens only after the decision is already made. Inevitable success has already been asserted, and now we are only waiting for our users to play the part they are supposed to play.

“Better than nothing” is worse than nothing

This type of validation will usually be pitched as “better than nothing,” as though you should be grateful.

And this (sadly, inevitably) brings us to the most “better than nothing” product of all time: generative AI. Because when the purpose of research is to cherry-pick favorable anecdotes from data, it doesn’t actually matter whether the data is real. In either case, it is the reader, not the author, constructing the meaning:

Vectors can be manipulated mathematically to look like meaning without having any externality of meaning … The real danger for me arises from the behaviour of the ‘recipient’ (the human reader) who ascribes patterns and meaning where there are none - who mistakes 'pseudo-language' for real language.

Harry Brignull takes us on a deep dive of why Synthetic Users, the flagship tool of the “better than nothing” field of user research, is a load of plausible nonsense. But this is not the only place LLMs show up in research. Industry heartthrob Anthropic is now advertising their bot’s ability to act as an independent researcher, which is horrifying if you actually take a look at its interviews and think about what Anthropic believes acceptable research looks like. This is no “PhD-level intelligence.” It consistently makes mistakes that even an undergraduate wouldn’t be allowed to get away with: leading questions, inserting its own meaning, and generally acting as a confirmation bias machine.

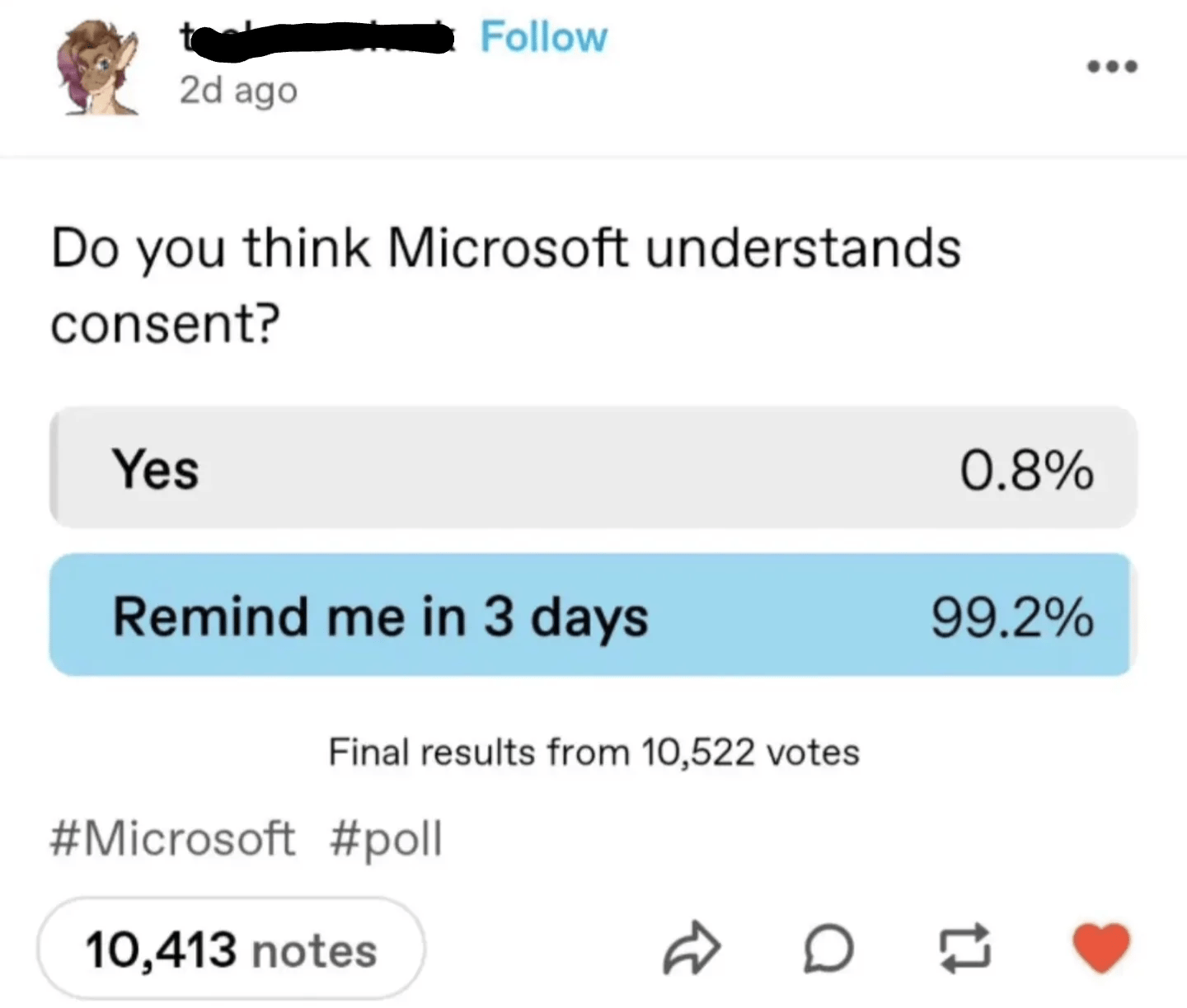

This kind of research epitomizes the “remind me later” world in which we now live.

This is not a “glitch” in the AI. The technology is not “going to get better.” This is a design decision; this is what Anthropic wants Claude to do. The success of LLMs rests entirely on affirming and reinforcing the prompts of its operator. It is an extension of the sycophancy that is trained into the model during tuning. It is a deceptive pattern without which the AI industry simply does not exist.

The opportunity cost of AI

It should be obvious that using these tools in your research destroys your ability to problematize the system you are studying. Instead, what you get is an onanistic feedback loop that interpolates within existing knowledge, forever. The individuating fibers — those unexpected moments that seem at odds with everything else you know, that signal untapped possibilities — are strained out. You fiddle around the edges. Order-of-magnitude improvements are not coming.

It feels like you are getting something for nothing (generated instantly, the energy costs externalized, the compute costs subsidized — for now) and so “better than nothing” is sufficient ROI. But you’re just taking out a loan against a future burden:

"AI" often means artificial intentionality: trying to trick others into thinking that deliberate effort was invested in some specific something. That attention that was never invested is instead extracted from the consumer— a burden placed on them.

And that burden manifests itself pretty much everywhere we’ve seen chatbot adoption:

Employers are now far more likely to reject high-quality applicants (19% decrease), and end up hiring an underskilled candidate (14% increase);

Where accuracy is important, employee costs go up alongside AI adoption: the more AI “speeds up” work at a company, the more time and money goes into checking that the work is actually fit for purpose;

Outright fabrications still slip through, leading to reputational damage;

The LLM’s output may look “close enough” but the actual work necessary to make it fit for purpose is colossal.

In all of these cases, filling in nothing with a “something” only absolved the chatbot’s user of responsibility. But the responsibility didn’t disappear; it was just transferred onto someone else. The alleged humans in the loop are swamped; senior leaders tell them that “productivity” and “innovation” are the most important things. They do the bare minimum to cover their own backs, and send the product downstream to the next hapless stakeholder.

What we can do about it

There is a defeatist streak within not only our industry but society in general. “It’s here to stay.” “If you don’t use it, you will get left behind.” These stock phrases get the cause and effect entirely backwards:

Instead of designing and using tools to build a society, society changes to adapt to the demands of our tools.

My favorite one of these concessions is one that seems the most innocuous at first; the wise middle ground between the skeptics and the boosters. “There are no bad tools, only bad people; you have to learn these tools in order to use them for good.” It is insidious because it paints the message as a moral obligation, and asks you to imagine capitulation to be resistance. Meanwhile, research shows the opposite: the more someone uses AI, the lower quality their outputs become. To understand the actual impact of LLMs, you’re far better off maintaining a critical distance:

We would expect people who are AI literate to not only be a bit better at interacting with AI systems, but also at judging their performance with those systems … but this was not the case.

There are many more of these stock phases, typically lifted straight from the marketing teams of AI companies. Gregg Bernstein writes a solid take-down of many that relate to research specifically.

But it is one thing to say no, and another to offer an alternative. Anil Dash rings in the year by talking about what the hell we are supposed to do now that tech and AI have become synonymous, which focuses on analyzing the system within which you work and finding leverage points beyond simply trying harder as an individual.

Once you have done that work, you might realize that we are being played for fools. The specter of AI casts a long shadow over our livelihoods. But when we try to push back against it — negate their argument — we are implicitly accepting its framing. “AI will take jobs, just not my job.”

That argument is still shaped like their frame. Instead, be like Kirby. Eat their frame:

And so we come back to “better than nothing” and the frame of that argument: that “there is nothing” was the whole problem, and by giving “something” we have solved it. It is brazen solutioneering. It is checklist thinking that allows executives to make it look like they did something.

The real choice is not between something and nothing, and it never has been. The real choice is between solving a problem and leaving it to fester. “Better than nothing” allows executives to pretend that they have done one, while actually doing the other.

The discomfort of “nothing” is a signal that someone’s duty was not carried out, a blinking red light on a dashboard. Breaking the lightbulb is “better than nothing.” The warning went away, and the pilot is off the hook up until the plane crashes.

Take Anil’s advice. Understand the system you’re a part of. But most importantly, identify whether your function is a need, or merely a want. Does your business model require that a thing be done well? Or is it merely satisfactory that it be done, and quality is someone else’s problem?

Needs get funding, and wants get “better than nothing.”

Remember: don’t assume that what’s happening is what’s supposed to happen — for example, that business decision-making about wants vs needs is rational:

The assumption that managers and business leaders make rational decisions based on quantitative analysis ends up making designers worse at storytelling, and then often sad and confused that the business case didn't work.

— Pavel at the Product Picnic