Howdy picnickers!

This one’s a bit late (I think beehiiv actually lets me backdate the posts but I’ll own up to it). Pre-writing these posts is tricky since I want them to stay fresh with the headlines and discussions that take place. However, a lot of issues have turned into essays rather than strictly speaking, newsletters. The format is always evolving; please let me know what you think.

Today, we continue with the final part of our discussion on why aimless outputs (sometimes rebranded to Just Doing Things) often produce negative value. In the first part, we talked about how “just doing things” causes work that is visible to crowd out work that is valuable; in the second part we looked at value production as a social system, made up of stakeholders and mental models rather than tools and artifacts.

We serve the social lives of ideas, helping them make connections … there is real work that goes into attending, to following curiosity and relating, and creating something novel but bringing others in.

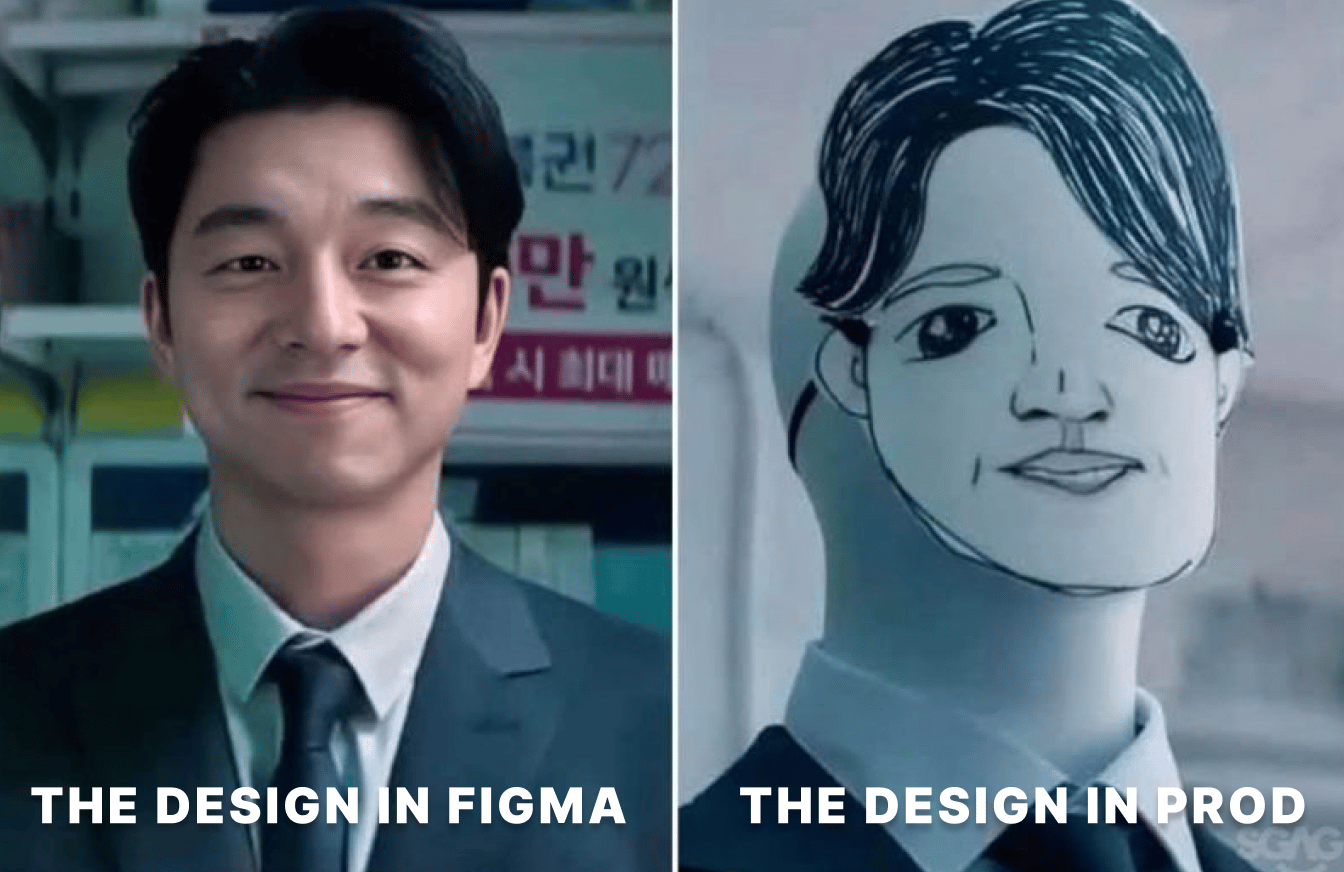

The laser focus on artifacts is a grave error, but a forgivable one. After all, our tools mainly produce pictures of websites — though this limitation has its upsides. Chris Coyier goes into quite a lot of detail to explain how overloaded our design tools would be if they had to deal with the full complexity of the Web up front. Code is a design medium, but not automatically the best one; deferring the complexity of code allows us to think more about the holistic experience we want to create, and iterate on those experiences more quickly and cheaply.

However, by the time the product delivery lifecycle has transformed those pictures into websites where a user can have that experience, the designs have gone through countless hands, and have not always survived the process intact.

“The designer should just write their own production code” is certainly one approach to solving this problem. But where does it stop? Should the designer also build the backend? Manage the AWS configuration? Compose the roadmap? Create the business case? Do sales? Learn fundamental physics and invent a time machine so they can fit all of these things into business hours?

At some point, unless you are a one-person indie shop, you are going to have to work hand-in-hand with another human being to deliver value to customers. And if your approach to Just Doing Things requires that no one else do anything without you there to make sure your vision is being faithfully executed, then you’re not accelerating velocity — you’ve actually become the new bottleneck.

Some managers might be thinking “AI can do it!” but that is a technology solution to a social problem, which has never worked for anyone. AI cannot engage with a social system because it has context, but not intent:

Content is defined by the intentional message present in the artifact; it is a way of transmitting something that embodies a perspective to an audience. LLMs do not have perspective, only context.

It can be hard for low-maturity product teams to tell the difference, however, because volume of artifacts has been used to disguise lack of intent for decades. And it doesn’t actually work! Testing two or three different versions with customers (a hold-over from advertising agency practice of putting two or three different versions in front of the client) is slower, more expensive, and less effective than just testing one version when you have a clear idea of what questions you want that test to answer.

Successive iterations of artifacts without intent creates significant conceptual debt for your product — not only because you don’t have the framework to determine whether a design decision is good or bad, but because those unintentional design decisions pile up. The individual building blocks may look really polished and test well, but when they come together within an unintended architecture, they are of no value to anybody. Eventually, that conceptual debt will come due.

Redesigning a product’s aesthetics is like Botox: something you can do as an outpatient. Redesigning the system’s semantic structures is like major plastic surgery: it requires general anesthesia and cutting into bone.

The most cost-efficient way of dealing with this debt is to avoid incurring it in the first place, by maintaining a shared mental model across the team for the entire duration of the project. The only way to do that is to cease surrendering control over what we want to say, and think about communication, not artifact, as the substrate of our practice.

All design (whether in code, in images, or in words) is theory-building before it is “crafting.” Employers are looking for people who know how to engage with the work at that level before diving into the nitty-gritty.

By the way, when people say “in the age of AI, designers should start doing strategy” this is what they are talking about — but it has nothing to do with AI. The fundamentals of our jobs haven’t changed. Designers should always have been doing this.

Not knowing how to communicate with our stakeholders has been the bottleneck in our impact for decades. If you want to stand out as a leader, this is where you need to start.

— Pavel at the Product Picnic